Leading change through dialogue is challenging but not as hard as trying to lead change without dialogue. To innovate during these fractured times, leaders must engage hearts not just minds, walk their talk, turn activists into allies, and have a bold vision without being domineering. With this approach, transformational change becomes possible.

Authentic dialogue among multiple stakeholders is an art. The leader is less in control of the outcome, which makes dynamics more alive but trickier. Perceptions of winners and losers mean some take fixed positions and block change from happening. Hidden agendas, whether real or perceived, scupper decision-making and coordinated action.

To cut through these obstacles, having parameters to guide the dialogue is a great resource. Understanding that there are four key principles to a dialogic process enables you to create an impact. Leading sustainable change is within the reach of any leader who’s open to work in an emergent, participative, and coherent way with their ecosystem of stakeholders. I cover two principles below and I’ll cover two in my next blog.

The ‘Sheffield Chainsaw massacre’

When I moved to Sheffield in 1998, I heard locals refer to the city as “an ugly picture in a beautiful frame.” Surrounded by the expansive moorland of the Peak District with its rounded hills, green valleys and limestone gorges, the city attracts ramblers, rock climbers and walkers. A saving grace of the city is being able to walk from densely populated residential districts into the heart of the Peak District through tree-lined, leafy streets.

Sheffield’s streets are home to 35,000 lime, ash, sycamore, cherry and rowan. Their large canopies create green corridors between rows of terraced houses flanking the pot-holed roads. Their sturdy trunks sprout leaves that brush against parked cars and pushchairs.

In 2012 Sheffield City Council decided to remove half of the trees and replace them with saplings. The reasons were unclear but pointed to making road maintenance easier and, as the old saying goes, getting rid of old wood. Many of the trees dated back to Victorian times and some had been deemed unhealthy.

The first tree was felled by the contractor in 2012, sparking a sense of outrage amongst locals. Activists organised demonstrations, launched petitions and collected signatures. Their umbrella group, Sheffield Tree Activist Group (Stag), set up a ‘flying squad’ of volunteers to stand under trees and obstruct works. Between 2016 and 2018 the police attended 40 tree protests and arrested 41 people. In 2018 Stag made an application for a judicial review which was rejected.

Following this, both sides dug in. The protestors used non-violent direct action but still two pensioners in their 70s were arrested. The contractor started work at 5am, waking up residents and asking them to move their cars.

The story hit the national headlines. MPs such as Michael Gove condemned the Council’s behaviour. Eventually an independent inquiry was carried out and published its results in March 2023. By this time, 5,600 trees had been removed and replaced by a similar number of saplings. Their conclusions included that the council:

- Had a ‘flawed’ approach and that its decision to remove trees was ‘misjudged’

- Was ‘deluded’ and had misled the public

- Had developed a ‘bunker mentality’ and eroded public trust

- Showed a ‘serious and sustained failure of strategic leadership’

The report wrote ‘The council had united almost everyone against them.’ It had pursued protestors for claims for damages which, if successful, would have made them bankrupt. It had caused high levels of stress amongst council staff and contractors, damaged its reputation and taken away the beauty of thousands of much-loved trees. One councillor faced prison. Although the roads, pavements and lighting ended up in better shape, it came at a very high cost. The report called it a ‘dark episode’ in Sheffield’s recent history.

The council eventually issued a lengthy apology last week (20 June 2023.) They acknowledged that many of the trees were healthy. Alison Teal, a former Green councillor, whom the council took to court for allegedly breaking an injunction that was enforced to stop protesters from protecting the trees from chainsaws, and was then found not guilty, tweeted: “It outlines the blindness of hubris and the unjust inclination of those with too much power to abuse it. A perfect case study for others to learn from.”

Four principles of dialogue

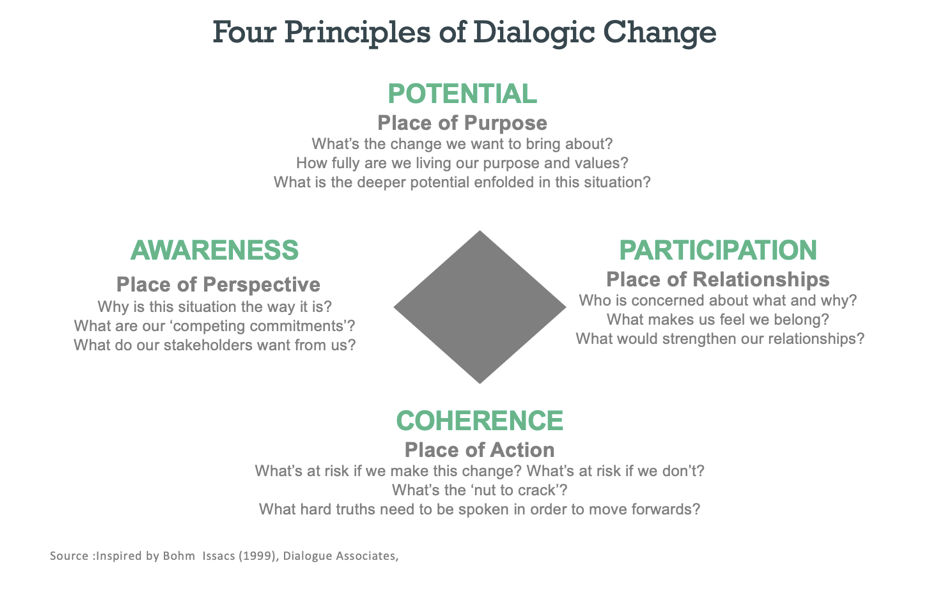

Embedded in this story are four principles of generating change through dialogue that were violated. When a leader acts in line with these principles, the change process is inspiring, inclusive, incisive, and intelligent. When a leader fails to work these principles, change becomes deeply problematic.

Each principle invites a distinct set of questions and invokes a specific stance for the leader. I cover two aspects below in more detail. See Figure 1 for an overview.

- Potential

When new possibilities flow into a meeting room, it energises people. Without a sense of potential, people perish. As Eleanor Roosevelt said, ‘The future belongs to those who believe in the beauty of their dreams.’

We saw in the ‘Sheffield Chainsaw Massacre’ story the impact of the City Council having no inspiring vision. The local people railed against their decision to fell trees as it felt like an unnecessary and unwise imposition. The reason for chopping down the trees was unclear as was the Council’s purpose.

By contrast when an authentic organisational purpose acts as a ‘lodestar’, it casts a direction for the evolution of the whole organisation. I’ll share the story of the Eden Project in my next blog and how the co-founders were attuned to the deeper potential of the disused clay pit and the possibility of being a ‘beacon of sustainability’ for others. The project managers used dialogue to explore what made people feel excited, energised, and proud to work for Eden. They tuned into the untapped wisdom of people, understanding that ideas lie dormant in unexpected corners. It’s the leader’s job to uncover them.

To activate the principle of potential, questions to explore include:

- What’s the change we want to bring about?

- How fully are we living our purpose and values?

- What is the deeper potential enfolded in this situation?

- Participation

When people feel ‘done to’, change becomes much harder. Change initially appears easier (to the leading party) as being directive is simpler and faster but it’s an illusion. When a heroic leader (or city council) ‘shows the way’, it often unravels through a failure to get buy-in. The need to manage resistance and enforce compliance drains valuable resources. Dealing with the fall-out of a ‘roll out’ takes much longer than a participatory change process, even if this latter approach seems slower to start with.

Change that sticks is a co-creation. It arises out of people making meaning together. At Eden, people talked time and time again about what it meant to be a ‘beacon of sustainability’ and how this would manifest in tangible actions. Change through dialogue is an iterative process of exploring an essential question together. It takes time to build a shared understanding, but the investment pays dividends. People are bought into change that they’ve been a part of creating, making even difficult change digestible.

The job of the leader is to get the ‘right’ people in the room at the right time. This means involving not just the potential champions of the change but the nay-sayers too. An insightful dialogue emerges when there are distinct voices that propose, support, challenge and reflect. You need all four to make positive change.

To activate the principle of potential, questions to explore include:

- Who is concerned about what and why?

- What makes us feel we belong?

- What would strengthen our relationships?