Deeper listening is one of the most critical skills that a leader can develop. When people feel heard, it unlocks collaboration, builds trust and allows new ideas to flow. Big doors swing on little hinges. Active listening is a vital hinge on which effective leadership pivots.

Twenty years ago, I decided to explore becoming a psychotherapist. Being a therapist would be more soulful than working a business psychologist, so I thought. I took an introductory course on counselling skills where the tutors taught us how to listen – and made us practice. It was only then that I discovered that true listening – rather than ‘re-loading’ and setting up my next point – required marshalling my attention in a conscious and deliberate way. I eventually abandoned my plans to enter the world of therapy – not just because listening was so demanding but because I also learnt that it was real human connection that I was after – and this can happen as much in a meeting room as on the couch.

Authentic dialogue starts, not with better speaking, but with better listening. The rub is, however, that many of us are not taught to listen. And, furthermore, listening – active, focused, giving-you-my-full-attention listening, takes time, energy and focus. The hard work does, however, pay off.

The power of active listening

Inspired by the work of Harville Hendrix, a best-selling author who has a PhD in psychology and religion from the University of Chicago, I’ve adapted his model of active listening in my team coaching work[1]. By making tiny changes to what they say, leaders can make real improvements in their ability to relate to their team members and other stakeholders.

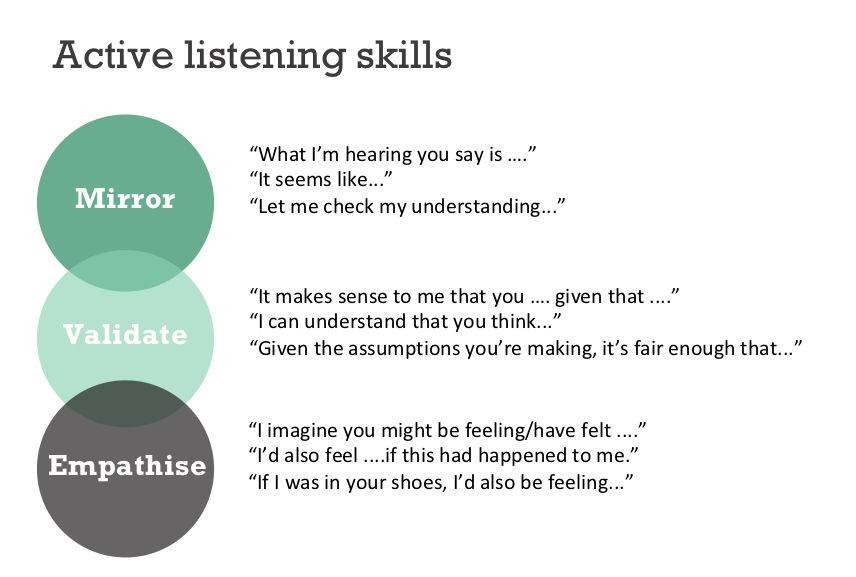

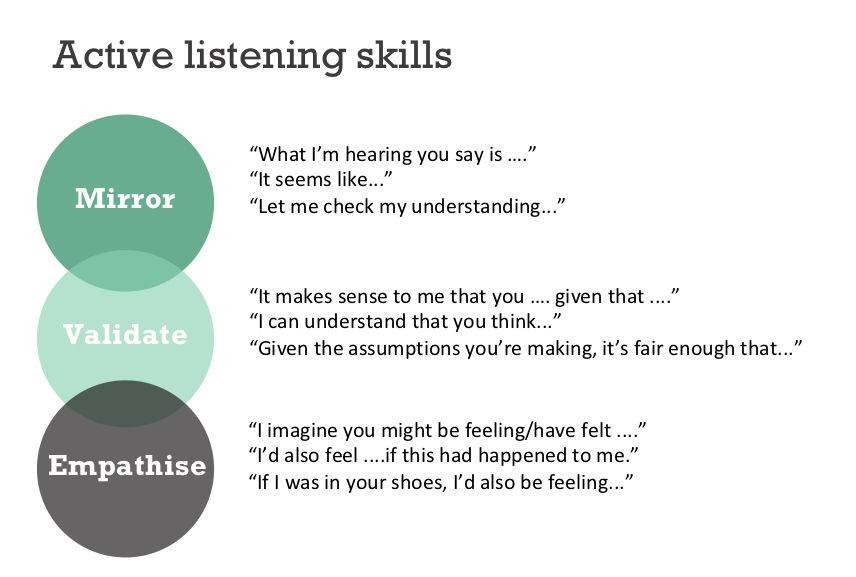

To practise better listening, three behaviours are key:

- Mirror. We repeat back to the other person they key things that they’ve said. We put aside our own stuff to concentrate on what the other person is saying. This attentive, active listening helps to people to become more aware of their thinking.

- Validate. We affirm that what the other person has said makes sense, even if we don’t agree with it. We seek to understand their viewpoint and acknowledge it as legitimate. By seeing the other as an equal, we come to understand their own ‘model’ of the world.

- Empathsise. We share how we imagine the other person is feeling or has felt. Here, for the first time, we add something of own perspective to the conversation. We take a guess about how the other person has been impacted and voice it, tentatively.

When people hear their own words played back, it helps to clarify their thinking. When differences in the assumptions people are making become explicit, it helps to unravel knots. By including people’s feelings, they feel truly heard. To give you the ‘nuts and bolts’ version, here are the actual words you might use:

Words to turn a conversation around

Recent research supports this approach to active, empathic listening. Elizabeth Stokoe, Professor of Social Interaction at Loughborough University, together with her colleagues, has analysed thousands of hours of recorded conversations, from customer-service interactions to mediation hotline conversations and police crisis negotiations. They’ve found that certain words or phrases – such as ‘Would you be willing?’ have the power to change the course of a conversation so that instead of a crash, the dialogue keeps going.

Another of the tiny, transformative phrases that Stokoe found made a real difference to the quality of our interactions is “It seems like…” I recently coached a team in a healthcare organisation where one of the turning points of the meeting was when one of the directors turned to another and said:

“It seems like you’re feeling frustrated that we tolerate underperformance and that we’ve been doing this for years. You want us to agree how to manage this collectively as a team. Am I understanding you right?”

Whilst others in the team were pushing ahead to agree a tangible way forward, the director who cared so passionately about improving performance was not ready to talk about practicalities until her position had been understood. By including some active listening, the conversation was then able to move on to more practical matters where the team eventually agreed a collective way forward to tackle the issue.

In the best-selling book, Difficult Conversations, Douglas Stone and his colleagues at the Harvard Negotiation Project underline the point that difficult conversations are, at heart, about difficult emotions. If emotions such as anger, disappointment and frustration are left unacknowledged, they don’t go away; they fester. Comparing them to ‘free radicals’ that hang around in the atmosphere, difficult feelings can derail a meeting, unless they are included. Wise is the leader who finds a way to bring them gently into the room without making anyone wrong.

In essence

Using active listening will enable you to communicate with confidence, influence and authority. There are subtle, yet profound ways in which the words we use shape our communication. Conversation and listening in particular is one of the most powerful tools that a leader can use.

Give it a go

Think back to a recent conversation you had which didn’t go so well. Replay the conversation as best you can in your head. At a key moment, press the pause button, and imagine that you turn to the other person and say:

“It seems like you’re saying…”

Do your best to summarise the essence of what the other person said. See if you can include something about how they were feeling – even if they didn’t directly speak to this. Feel into their position; stand in their shoes; imagine how you might feel if you were them.

[1] Getting the Love You Want (1988) Harville Hendrix.