I’ve been leading several sessions recently on having courageous conversations. One of the things I cover are the obstacles such as lack of time, fear of upsetting someone and not knowing how to get started (I know a great book that can help you with all these aspects! 🙂 ). High on the list of the ‘blocks’ is the common perception amongst some managers that there’s a tricky colleague who makes dialogue impossible. Perhaps someone immediately springs to your mind? Maybe there’s someone in your team who’s rude, demanding or mean? Dealing with the nay-sayer, troublemaker or even grumpy person can cause many a wrinkled brow if not sleepless night. It could be your boss who has a habit of making inappropriate remarks, a direct report who repeatedly turns up late or a senior leader who never replies to your emails.

Having coached many teams over the years, I’ve seen first-hand how dialogue turns ‘difficult people’ into valuable assets. When team members have the tools to give each other feedback (in a short, structured, safe one-on-one setting), it lifts and shifts the whole team dynamic. After I’d led an IT team through a ‘feedback carousel process’ (where they each paired with every other person), one ‘difficult’ person reflected: “It’s easy to ignore another person’s comments about you but when I hear the same thing seven times over, I have to pay attention.” As a result of making it safe to share feedback, collaboration amongst team members significantly improved. It’s possible to draw the brilliance out of bolshy people by having a real and respectful conversation.

What happens if we don’t lean in

If there’s a so-called ‘bad apple’ upsetting the applecart, left unaddressed, there are several dangers. Meetings might be run with the sole intention of not upsetting that person. Team members become frustrated with the lack of progress. The atmosphere turns toxic as people gossip rather than discuss what really matters. We might be tempted to sink to their level. The problem is if we back-bite, others bitch. If we complain, others gripe. If we go silent, someone else’s cold shoulder also sets in.

Below I’ll come to some strategies for ‘leaning in’ rather than botching the conversation or avoiding the person. The latter approach rarely works as Isabel Berwick, writing in the Financial Times, notes. When she asked Michael Skapinker, a former FT colleague and now a work and retirement counsellor, for his advice on how to handle a toxic colleague, his most helpful suggestion was to “disarm the person by asking what would make their work easier. Repeat what they say back to them. Ask them what they think the best solution is. Toxic people are often hiding insecurity 🫣. Being taken seriously may make them more tolerable.”

Whilst this is good advice, it leaves us at the mercy of the other person being willing to engage. Another approach (that I write about in my book, Now We’re Talking) is to switch your focus so that instead of focusing on the difficult other person, you place your attention on what you can change: yourself. Whilst it’s true that some people are disrespectful, volatile or undermining, you can rarely do anything to change them; all you can do is to ‘keep your own side of the street clean’ (for more input – see the questions below.)

Rethinking collaboration

A recent interview carried out by Egon Zehnder with author and dialogue practitioner, Adam Kahane (I’ve been a big fan of his for years) also got me thinking. In this thought-provoking interview, Adam Kahane invites us to rethink a common assumption in leadership and collaboration: that some people are simply “too difficult” to work with and must be managed, avoided, or controlled. Drawing from decades of experience facilitating dialogue in some of the world’s most polarized contexts – from post-apartheid South Africa to the Colombian peace process – Kahane offers a compelling alternative. Here are some key takeaways:

- Collaboration doesn’t require alignment on values. We often believe that we need shared beliefs, plans, or trust to collaborate. Kahane argues this is a myth. Progress is possible even with people we don’t like, agree with, or trust.

- The people we least want to work with are often the ones we most need. Especially in complex systems, those in power or with strong (even toxic) personalities may be essential to the solution. The challenge isn’t to fix or exclude them, but to stretch ourselves to engage.

- Humility is the superpower. Successful collaboration across differences isn’t about dominance or righteousness. It’s about humility – valuing others’ perspectives without needing them to match our own.

- Let go of the idea of ‘dealing with’ others. Instead of seeing people as problems to be handled, Kahane urges us to ask: What’s my role in this situation? What’s mine to do to move things forward – together?

In summary, it’s not about finding the perfect partner, but about doing the work. Collaboration is less about harmony and more about doing what’s necessary, even when it’s uncomfortable. As Kahane puts it, “You can’t collaborate with everybody on everything, but you can often do something important with someone—even if you’ll never agree.”

Kahane’s perspective liberates us from the exhausting task of trying to “fix” difficult people and instead invites us to become more agile, self-aware, and committed to collective outcomes. It’s not about taming others – it’s about transforming how we show up.

How to get on with anyone

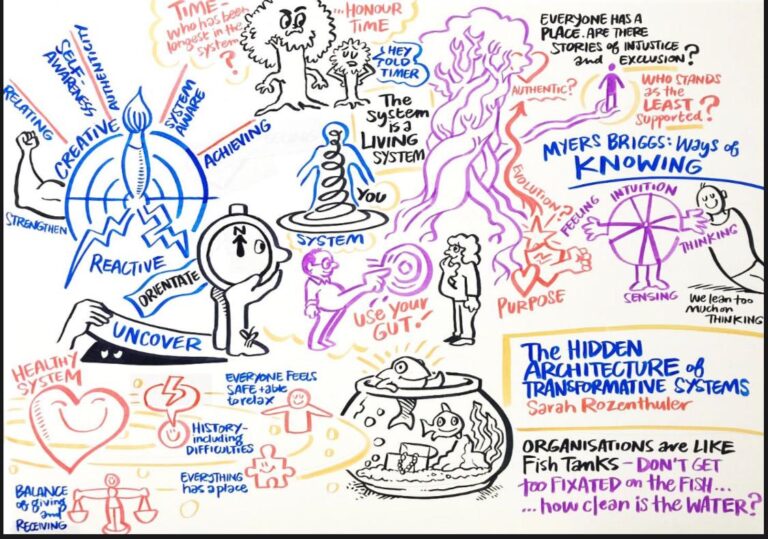

Finally, you might find further inspiration in listening to my recent conversation with Catherine Stothart, author of How to Get on With Anyone. This book offers a practical communication model rooted in personality psychology, specifically adapted from the Interaction Styles™ framework developed by Linda Berens. This model helps individuals understand their own and others’ communication preferences so they can build better relationships at work and in life including when things seem difficult

One benefit of Interaction Styles is that it links the overall patterns to underlying tendencies – towards extraversion or introversion, and towards a directing communication style or an informing communication style. Exploring these tendencies makes it easier for people to recognise their own style, and to identify specific concrete actions that they can take to connect with others.

The Interaction Styles framework is different from some other personality frameworks. Like other personality models, such as MBTI® and Insights Discovery®, it also draws on Carl Jung’s theory of psychological types. What’s different is that it includes an important distinction between how we attempt to influence others, either by a more direct way of communicating or a more informing style.

Some of us prefer to ask someone directly, for example, to “please write the minutes.” Others of us will take a different approach and say, “It would be useful if someone could take the minutes”. Taking time to reflect on our preferences and then ‘style flex’ when talking with someone very different to us pays dividends. Catherine shows us the way.

In closing

Perhaps there are no “difficult people” after all – only difficult dynamics that call for courage, curiosity and care. When we shift from judging to listening, from reacting to inquiring, something begins to soften. We start to see the human being behind the behaviour.

The next time you find yourself labelling someone as “hard work,” pause and ask yourself:

- What story am I telling about this person?

- What part might I be playing in keeping this dynamic stuck?

- What question could open a new conversation between us?

As Adam Kahane reminds us, collaboration doesn’t depend on liking or agreeing – it depends on showing up. And when we do, with humility and intention, even the toughest relationships can begin to transform.

Over to you

If this topic resonates, take a small but meaningful step this week: have one courageous conversation you’ve been postponing. You might be surprised at what shifts when you engage with empathy and openness

For more practical tools and stories about turning tension into connection, explore my book Now We’re Talking — or get in touch if your team could benefit from learning how to talk, think and thrive together.

References

Collaborating Across Differences, An interview with Adam Kahane by Egon Zehnder, July 2025

https://www.egonzehnder.com/insight/collaborating-across-differences

Stothart, C. (2024) How to Get on With Anyone. Pearson

Isabel Berwick, (30 July 2025) Financial Times Working It, Office Talk

Rozenthuler, S. (2024) Now We’re Talking: How to discuss what really matters. Pearson