Open communication is motivating for groups who need to innovate. To stimulate this, leaders in these disruptive times need a communication competence that fosters dialogue. As I said in my previous post: Leading change through dialogue is challenging, but not nearly as hard as trying to promote change without this.

There are many obstacles to leading change effectively. Chief amongst these is a lack of dialogue. As Nancy Rothbard (Deputy Dean and Professor of Management at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania) has said: The sinkhole of change is communication and motivation. It’s where change projects go to die.

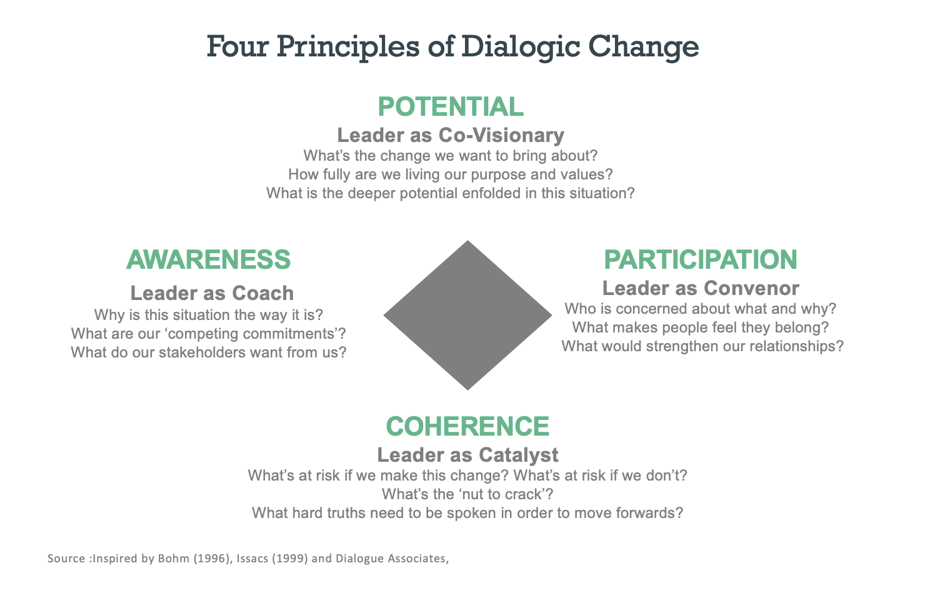

We often say a leader should ‘walk their talk’: Let’s talk about the walk of dialogue. Understanding the four key principles of a dialogic process enables you to shift how you see your role and so create a positive impact. I covered two principles in my previous post (Potential and Participation); here are the principles of Coherence and Awareness. When a leader recasts their role from manager/controller to being a co-visionary and convenor as well as a catalyst and coach, leading sustainable change becomes possible.

A Tale Of Change

A common oversight in leading change is focussing too much on the ‘what’ of change (a new strategy, operating model or organisational structure) and not enough on the ‘how’ (such as having a shared vision and getting the right people to have the right conversation at the right time.) Here’s an example of change done well (in my previous post, I included a story of change done badly), and the pivotal role that dialogue played in the change process.

Finding Eden in Cornwall

The Eden Project is an visitor attraction in southwest England, located in a reclaimed pit where for 160 years the land had been used for china clay extraction. Tim Smit, a Dutch-born British businessman and Jonathan Ball, a Cornish architect, co-founded the project which the Guardian has called a “mind-boggling feat of both architecture and biological engineering.”

After work began in 1995, the centre opened in 2001 on a mission to create a ‘living theatre of plants and people’ and a ‘refuge for the world’s endangered species.’ It has become famous for its two huge greenhouses known as ‘biomes’ which grow a vast array of plants including massive banana trees in a temperature-controlled environment. It’s an impressive achievement given the wet and chilly Cornish climate. A scar on the landscape has been transformed into a place of beauty and inspiration with over 1 million visitors a year. Smit has claimed that the Eden has contributed over £1 billion to the Cornish economy.

In 2006, the project entered a new phase of work with the construction of an education centre. When I visited the building in 2008 to run a wellbeing workshop, I found the light-filled, spacious rooms with their lawn-green carpet tiles highly conducive to having great conversations. My ‘A New You’ workshop was all about giving people back a sense of worth through an expansive dialogue about our true nature and the rooms really sustained our work together.

The intention for Eden was to become recognised as an ‘exemplar of sustainability’ and mobilise the organisation towards more ecologically sustainable ways of operating. Donna Ladkin, a professor of leadership at Birmingham University, has written a case study about this phase of the work in her book Rethinking Leadership. She attended meetings on site, interviewed people involved in the construction and spoke with two key personnel. There are many verbatim quotes including one from the project manager, Andy Cook, who said:

“I’ve never been involved in a project where you just had to keep talking and talking and talking so much… It became clear that no one person had the answer to how to be an exemplar of sustainability. We had to talk together to figure out what it might mean. It was kind of like a puzzle, everyone had a piece of it. I began to see my job as just getting the right people in the room together with the right knowledge so that we could figure it out together.”

The two project leaders reflected on how their role was to help connect people from different professions and departments. They explored how their jobs contributed to the big picture purpose and were open to their answers. They were sensitive to the need for ‘glue’ to motivate people to continue to engage. They tapped into feelings of pride, excitement, and enthusiasm for the project, generating goodwill and a willingness to work together.

They asked people a recurring question: What does it mean to be an exemplar of sustainability? It was a contested concept; the ‘lived’ meaning had to emerge as people debated decisions, took action and evaluated impact. Some broad agreements gradually emerged, such as not using PVC in any of the buildings, engaging local contractors and aiming to produce zero waste. Asking the ‘right’ question was not easy but doing so distinguished authentic dialogue – which actively pursues difference – from inauthentic dialogue – which constantly narrows and restricts possible meanings.

The creation of meaning is a dialogic endeavour. It emerges from conversations between leaders, team members and other stakeholders. Ladkin asks: ‘Can a vision be heartily adopted if the ranks serve only as recipients of the vision? What if they don’t believe in the vision?’ She reflects that constructing meaning through dialogue might often be more appropriate than unilaterally uttering declarations. The leader ‘holds the purpose’ but the ‘lived meaning’ is co-created between those participating in a creative dialogue. Staying in dialogue enabled people to tune into ‘right action’; actions that were coherent with the organisation’s purpose.

Only through dialogue can a ‘fusion of horizons’ emerge. Ladkin concludes that the role of a leader is not to pronounce the way forward but to provide a safe and stimulating space where ‘inquiring conversations’ can occur. This is a messier type of engagement than a heroic leader who ‘shows the way’ with their preconceived and rarefied vision that they then try to get others to buy into. Here leading change successfully involves letting go of control and inviting others to contribute, in a spirit of openness, inclusion and curiosity.

Four principles of dialogue

Embedded in these two stories are four principles related to generating change through dialogue. Each principle invites a distinct set of questions which I outline below (see Figure 1.) These questions are not an exhaustive list. The energy of them is more important than the content. The questions act as ‘seeds’ for generating change through dialogue. When a leader grapples with these questions, their conversation creates change that sticks.

All four principles call on a leader to re-imagine their sense of identity. The overall shift is from being a manager, who deals with certainty and control (or the illusion of certainty and control) to being a leader who values the potency of uncertainty, and the collective. When a leader sees themselves not as a commander-in-chief but as a co-visionary, convenor, catalyst and coach, real change becomes possible. Their shift of identity creates the ground upon which an authentic dialogue can take place.

Figure 1 – Four Principles of Dialogic Change

- Coherence

Dialogue produces change when it leads to people taking ‘right action.’ By this I mean, people take action that is in alignment with the organisation’s purpose and which benefits the whole rather than just themselves. It takes time to surface ‘right action’ as this arises out of a shared understanding of what the issue is.

Decades of research has uncovered many different biases that lead to poor decisions and incoherent actions. When these biases remain unexamined, making change sustainable becomes much harder.

Instead of enrolling others into their way of thinking, an effective change leader sees themselves as ‘the keeper of a context where dialogue can happen’ (Bob Anderson.) They bring a focus on learning, shared understanding and sense-making. A leader acts as a catalyst who addressed fixed mindsets and expands other peoples’ thinking. They are open to change, willing to be challenged themselves and ask clarifying questions such as:

- What’s at risk if we make this change? What’s at risk if we don’t?

- What’s the ‘nut to crack’?

- What hard truths need to be spoken in order to move forwards?

Ladkin points out that asking questions and listening to the answers you hear is an important way that we learn about our prejudices. When someone says something that does not make sense to us, we are ‘pulled up short.’ This ‘jolt’ can help to reveal a prejudice we were carrying that we weren’t previously aware of. Such moments also make it clear that actions need to be jointly negotiated. Each person holds a piece of the puzzle and no one person holds the whole puzzle.

2. Awareness

Dialogue becomes a tool for transformation when people talk about what matters most. As people share the truth of their experience and listen to the experience of others, they are more willing to discuss risks, share fears, and name the ‘undiscussables.’ The more real the conversation becomes, the more possible it is that the assumptions and beliefs that shape collective reality surface. Becoming aware of these underlying beliefs means that people can examine them and even upgrade them, making outer change possible.

In their classic HBR paper, The Real Reason People Won’t Change, Kegan and Lahey highlight a key psychological dynamic that makes people ‘change-resistant.’ They call this a ‘competing commitment.’ It is often unconscious and yet has a powerful influence.

Hidden loyalties cast a long shadow over our experience unless we become aware of them, particularly in a collective context. A Board of a start-up might say that they want to lead a world-class organisation but staying with a more random, entrepreneurial way of operating that many are still bought into will make it hard to shift away from the pattern of ‘going where the energy is.’ Unless a ‘competing commitment’ is aired, shared, and discussed, it will run the show from behind the scenes.

To activate the principle of awareness, it calls on the leader to be a coach. Instead of asserting the way forward, they become curious and ask questions:

- Why is this situation the way it is?

- What are our ‘competing commitments’?

- What do our stakeholders want from us?

When people access a deeper level of awareness, this remains available after the dialogue has ended. Dialogue leaves people feeling like they’re a bigger version of themselves, both individually and collectively. As a result, a disparate group of individuals starts to operate as a whole. As limitations to thinking loosen, new insights and intuitive flashes appear. The group harvests the wisdom and newness in the room.